The COVID-19 outbreak has led to, among other things, an unprecedented use of the word unprecedented and a flurry of articles that attempt to diagnose the supply chain issues experienced in this pandemic.1 These articles lay the blame firmly at the feet of just-in-time (JIT).

Financial Times, for example, suggests that “companies should shift from ‘just in time’ to ‘just in case,'” Business Standard warns that time is running out for just-in-time inventory systems while Supply Chain Dive proclaims that “today’s supply chains are too lean.”2-4 One journal has even accused JIT of something far more serious: “How ‘just-in-time’ capitalism spread COVID-19.”5 Unprecedented indeed.

I read these articles, as well as others in The Loadstar, The Maritime Executive and The Grocer.6-8 There are some good points made and relevant factors are identified.

But this raises a question: Has COVID-19 exposed deep-seated flaws in the Lean philosophy itself, or simply exposed the shortcomings of our understanding of it? Let’s revisit JIT in its original context in order to arrive at a more nuanced view of the role of Lean methodologies in this pandemic.

JIT is arguably the most well-known feature of Taiichi Ohno’s Toyota Production System (TPS), the principles of which later became enshrined in the workplace efficiency philosophy known as Lean. While Henry Ford in North America had huge warehouses filled with mass produced stock, Taiichi Ohno manufactured small batches with more variation and no storage – which crucially resulted in lower costs and higher quality. Stock was simply produced when it was required – not before. This meant that defects were identified immediately, expensive storage space was redundant, and no time or effort was wasted moving stock to a warehouse and back. Stock was therefore produced just in time for when it was needed, with the empty crate returned to trigger production of the next batch.

The car manufacturing industry was revolutionized with this new way of thinking and the idea quickly spread throughout manufacturing and beyond. It is now rare to walk onto a factory floor that does not use JIT.

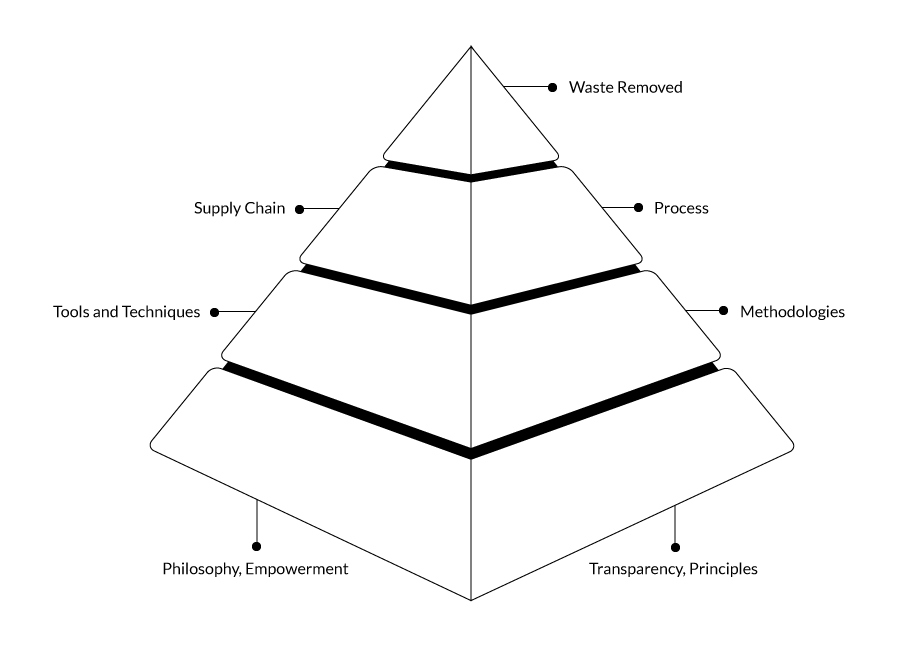

But JIT was never designed to be a standalone principle and its creators certainly never intended for it to be applied rigidly, outside of the context of Lean philosophy. JIT was one of many paradigm shifts that Toyota went through to get from mass production to Lean production.

Lean was never intended to be a fragmented set of prescriptive tools, but rather a philosophy to underpin all values, methodologies and tasks. Many managers profess to want good results, but few want a culture of no blame. Many want to cut costs, but few want to eliminate waste. Lean tools are quick to be adopted but the Lean philosophy is often neglected.

The TPS was born from a visit to Henry Ford’s North American factory, where Taiichi Ohno instantly recognized that Ford’s set up could never work in the context of Japanese manufacturing. We would do well to return to the core philosophies at the heart of Lean. To eliminate waste and continuously improve, we must evolve our methods within their context. As Ohno himself said, “You are a fool if you do just as I say. You are a greater fool if you don’t do as I say. You should think for yourself and come up with better ideas than mine.”

Rigidly applying an East Asian car manufacturing principle from the 1950s to a modern-day global supply chain without questioning the context would certainly have Ohno saying “Oh no.” JIT is a great starting point, but a true Lean mindset will adapt it from its original context to modern manufacturing, supply chain, the service industry and beyond.

When Toyota implemented JIT, the result was not a cutthroat relationship that stretched suppliers beyond their limit, holding a gun to their head in order to satisfy the mystical nirvana of “zero inventory.” It was quite the opposite: Toyota took great time and effort to learn about their suppliers, to understand their costs and challenges. They created frameworks based on mutual benefit – a cooperative relationship, which was never terminated on the grounds of under-delivery as long as the supplier was showing effort to improve.

Toyota used the 5 Whys to help their suppliers get to the root cause of their problems, rather than threatening to change supplier on the grounds of quality. Their pricing model was built on the assumption that both supplier and manufacturer would receive a reasonable profit. Furthermore, Toyota allowed their suppliers to keep any profits created from their improvement efforts, rather than lowering the final product price accordingly.

This builds a different picture to the aggressive supply chain models that are now under so much pressure from COVID-19. With so many companies operating under a self-proclaimed banner of Lean or JIT, I worry that the original message got lost in translation.

Maintaining a Lean culture, which informs constantly evolving methodologies, is dependent on identifying problems and continuously improving. Lean philosophy is driven by identifying anything less than 100 percent efficiency and quality. Ohno explained, “Having no problems is the biggest problem of all.”

With this in mind, COVID-19 gives us a unique chance to reconsider our business practices in light of current issues. When Taiichi Ohno walked around Henry Ford’s factory, he was struck by the large amount of muda (waste). As we settle into our remote working routines, we, too, are discovering that some things that we thought were value adding, are actually unnecessary.

I propose that as we consider our business response to COVID-19, we take a truly Lean approach. See JIT in the context of Lean and evolve it as necessary, using the change in environment to identify waste (anything the customer does not want to pay for) and see new problems as opportunities for new improvements.

References

- Wittenstein, Jeran. “‘Unprecedented’ Has Become Corporate America’s Go-To Descriptor,” Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-04-22/-unprecedented-has-become-corporate-america-s-go-to-descriptor. Published April 22, 2020. Accessed July 3, 2020.

- “Companies should shift from ‘just in time’ to ‘just in case,'” Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/606d1460-83c6-11ea-b555-37a289098206. Accessed July 3, 2020. Subscription required.

- Das Gupta, Surajeet. “Covid-19 outbreak: Time running out for just-in-time inventory system,” Business Standard. https://www.business-standard.com/article/companies/covid-19-outbreak-time-running-out-for-just-in-time-inventory-system-120042800072_1.html. Published April 28, 2020. Accessed July 3, 2020.

- Weissman, Rich. “Today’s supply chains are too lean,” Supply Chain Dive. https://www.supplychaindive.com/news/lean-supply-chain-jit-inventory-covid-19/574693/. Published March 24, 2020. Accessed July 3, 2020.

- Moody, Kim. “How ‘just-in-time’ capitalism spread COVID-19,” MR Online. https://mronline.org/2020/04/13/how-just-in-time-capitalism-spread-covid-19/. Published April 13, 2020. Accessed July 3, 2020.

- Morrow Roberson, Cathy. “Comment: Coronavirus may mean the end of just-in-time, as we know it,” The Loadstar. https://theloadstar.com/comment-coronavirus-may-mean-the-end-of-just-in-time-as-we-know-it/. Published March 23, 2020. Accessed July 3, 2020.

- Fraser, Evan. “Op-Ed: COVID-19 Reveals the Risks of the Just-in-Time Supply Chain,” The Maritime Executive. Published March 20, 2020. Accessed July 3, 2020.

- Holmes, Harry. “Food security: are we cutting food too fine with our just in time supply chain?” The Grocer. https://www.thegrocer.co.uk/supply-chain/food-security-do-we-need-to-rethink-our-just-in-time-supply-chain-post-coronavirus/604872.article. Published May 14, 2020. Accessed July 3, 2020.